DERBY AREA SIGNALLING

"The Peckwash Mill Disaster"

This article has appeared previously in the Journal of the Midland Railway Society.

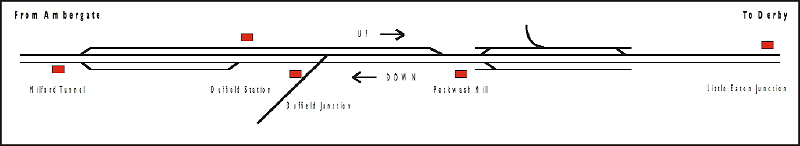

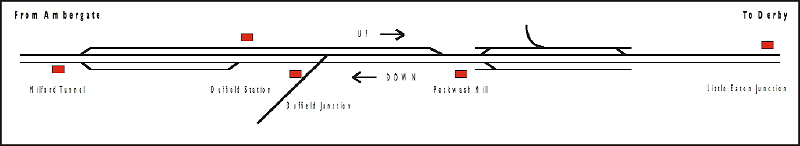

In contemplating the events of Saturday, 1st December 1900 at Peckwash Mill Sidings, it is necessary to first have an understanding on the railway geography of the area.

Like most railway installations, Peckwash Mill Sidings evolved slowly over time. Midland Railway records tell us that there was a signal box here by 1877, a time when the practice of centralising control of points and signals in a cabin was only just becoming the norm.

The Peckwash Mill, which led to the provision of Peckwash Mill Sidings, owed its existence to the proximity of the River Derwent, the power of which spawned the Industrial Revolution. Mills of one variety or another sprang up all along the Derwent Valley. This particular mill was built by Thomas Tempest in 1805 as a paper mill.

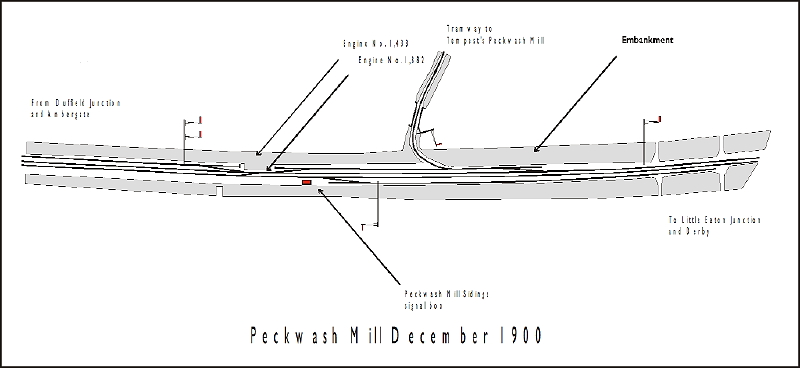

The mill is on the opposite side of the Derwent to the railway and was initially served by a short tramway running at right angles to the main line. A wagon turntable formed the connection with a single siding on the ‘Up’ side which opened for traffic on 15th December 1877.

Expansion characterised the railways of the Eighteenth Century and the Midland Railway’s North Midland line had reached capacity by the end of the century. The solution was to ‘quadruple’ the route where the topography allowed it. Consequently a third line was added to form an Up Goods line between Duffield Station and Peckwash Mill. The proximity to the river required the railway to be built upon an embankment to keep it above the winter flood level, meaning the provision of extra lines was no easy task.

It was Milford Tunnel to the north of Duffield which dictated the commencement of the Goods Line. That it should end at Peckwash Mill was always intended to be a temporary state of affairs, brought about by the convenience of already having a signal box there to control the junction.

That said, the existing structure, as was the Midland Railway’s practice, would have been a tiny 10’ square “Type 1” cabin, barely large enough to accommodate its existing frame which, in turn, would have been sized according to what it controlled. Thus a new signal box was opened on 14th March 1897 preparatory to the Up Goods Line being taken into use on 4th October 1897.

By now the wagon turntable had been replaced by a direct connection from the Up Siding to the Peckwash Mill line. As the formation crossed the Derwent flood plain, a substantial earthwork was required to carry the line on an extremely tight curve. Even so, the line didn’t warrant the term ‘branch’, remaining a humble ‘tramway’. The Ordnance Survey map of the period also shows a ‘lie-by’ siding on the Down side.

The existing Up siding was not altered by the building of the Up Goods Line. In due course the Goods Line would be extended southwards to Little Eaton Junction and a new Up Siding provided alongside it. In the interim, however, the two lines butted up to one another with their respective stop-blocks back-to-back some 50 yards apart. History records that the embankment between the two stop-blocks was not built up, thus leaving a drop down to the drainage ditch at the foot of the bank.

Like its predecessor, the 1897 Peckwash Mill box was located on the Down side and was to survive almost to the end of mechanical signalling in the area. Sited across the line from the 132¼ mile post, it was 1 mile 291 yards from its southern neighbour at Little Eaton Junction and 1,236 yards from Duffield Junction to the north.

Midland Railway signal boxes were remarkably standardised and Peckwash Mill was a quite rare example of a box being 12’ 6” deep (i.e. front to back), the norm being 10’. Whereas the original box probably had a frame of no more than ten levers, the later box had 32, of which only three were spare at the height of its operation.

In contrast to the widely praised “Rotary Interlocking Block” employed by the Midland Railway on most of its passenger lines, the method of working on goods only lines, and which perpetuated well into the middle of the Twentieth Century, was much less laudable. As with any system of “Block” signalling, bell signals were used by the signalman to describe the nature of train approaching the next section as well as to announce its entry into and departure from the section. The difference with this system, known as Telegraph Bells, that there was no visual reminder to the signalman as to what trains were in his Section. Unlike “Absolute Block” used on passenger lines, Telegraph Bells was a “Permissive” system. That allowed any number of trains to enter a section whereas the Absolute system was strictly one at a time. Granted, the second and subsequent trains to enter a Permissive section were stopped or otherwise warned that the section was occupied but it was the lack of visual indication that led to its eventual replacement by a more conventional Permissive system.

At Peckwash Mill the main (or Passenger) lines were signalled under the Absolute system with Rotary Interlocking Block whereas the Goods line was signalled by Telegraph Bells. As a consequence of allowing more than one train into a section there was no need to break the line up into short Blocks. A signal box was only really required where the trains were to be stopped. In the case of the newly installed Up Goods as there were no connections at Duffield Junction the signal box there had no need to control the trains. Therefore the next signalbox “in rear” of Peckwash Mill on the Up Goods was Duffield Station.

This resulted in a situation whereby the signalman at Duffield Junction played no part in the signalling of trains on the Up Goods line, although it has long been the rule that signalmen would be expected to observe the passing of all trains, regardless of whether they were under their control or not, to ensure their safe passage.

We now turn our attention six miles to the north where at 2.35 a.m. in Ambergate North Junction yard driver Henry Hitchcock and fireman Frederick Teagle, took charge of the 4.50 p.m. mineral train from Shirland Colliery. The train was destined for Chaddesden Sidings where it was due to arrive at 4.30 a.m.

Hitchcock, a married man of 33 years of age, entered the employ of the Midland Railway in 1889 as an engine cleaner, being made fireman in 1890, and driver in October 1899. He belonged to a “most respectable family”, nearly every member of which was engaged in railway work. His father, also Henry Hitchcock, was a foreman at Chaddesden sidings, where he was very much respected. Of his other brothers, two were drivers on the Midland, one a driver on the Great Northern, two were drivers in Canada, and another was employed in the Midland Carriage Department at Derby. To add to the subsequent confusion, his sister married another engine driver, whose name was also Henry Hitchcock.

Teagle, who was a single man of 22 years of age and hailed from Sileby, Leicestershire, entered the Midland service as a cleaner in 1898, and was made fireman in 1899.

Hitchcock & Teagle were shunting for about an hour at Ambergate. Arthur Quinby, the train guard said this was carried out in the usual way, and before leaving Ambergate, he saw both the driver and fireman on the engine and told the driver they were right away to Chaddesden and what they required to do at their destination. Hitchcock replied to the effect that he quite understood and Quinby did not notice anything unusual with him.

They left the sidings at Ambergate North Junction at 3.30 am. on their run south. The train consisted of a six-wheels-coupled tender engine No 1,433 running chimney first, fitted with a steam brake, 44 wagons loaded with coal limestone and lime, and five empty wagons, with a ten-ton double iron blocked brake in the rear – a total length of about 320 yards. The train was not especially heavily loaded.

It was a dark night and rain was falling slightly, resulting in the rails being described as ‘greasy’. There was no fog and the signals were clearly visible. In his 14 months as a driver Hitchcock had become quite familiar with the road and on this clear night, is unlikely to have had any difficulty with his surroundings.

The train had no booked stops between Ambergate and Chaddesden sidings and the signals were off for it to proceed at all the signal boxes between Ambergate and Duffield. At Milford they left the main line and at 3.45a.m. proceeded through Duffield on the Up Goods line at around 15 miles per hour.

Meanwhile, the 12.40 a.m. Class ‘A’ Rowsley to London express goods train driven by John Walter Partridge was approaching Duffield on the Up Passenger line with all signals off. The train consisted of a six-wheels-coupled tender engine, No. 1,882, running chimney first, with 30 wagons and a guard's brake at the rear.

In the signal box at Duffield Junction, signalman Edwin Barnes – a man with 28 years service, 23 years at this box – offered the express goods to his colleague at Peckwash Mill. In the latter box was Sidney Stiles, a less experienced man with a mere nine years signal box service to his credit and just nine weeks at Peckwash Mill. Stiles accepted the Class ‘A’ goods from Duffield Junction at the same time as he received the “Train Entering Section” bell from Duffield Station for the mineral train.

The Class ‘A’ was ‘asked on’ to Little Eaton Junction and was accepted so Stiles ‘pulled off’ his signals for the express goods. This action would, of course, lock the Peckwash Mill sidings Up Goods home signal and its distant signal at danger.

As his brake van at the rear of the mineral train was passing through Duffield Station, Arthur Quinby went out onto the platform of his van. He saw that the Duffield Junction Up Passenger home signal and Peckwash Mill Up Passenger distant below it were both ‘off’. At this time the engine of his train was just passing the Peckwash Mill Up Goods distant which he saw was resolutely ‘on’.

At this point, the train was on a falling gradient varying from 1 in 383 to 1 in 418, and the curvature is inconsiderable. As has already been mentioned, the drizzle had resulted in the rails being greasy – a challenging combination for a driver stopping a heavy unfitted goods train.

Quinby considered that the 15 miles per hour that he estimated his train’s speed at to be “somewhat greater than usually the case under similar circumstances” and at that moment, although the driver had not ‘whistled’ for the brake, he felt the driver commence to check the speed of the train, and he applied his hand brake to assist in doing so. When later asked the direct question whether he was ‘alarmed’ at the speed his train at this point, Quinby told the Coroner “Well, no, but I thought he was going a bit too fast”.

In Duffield Junction box, Barnes was similarly ambivalent; He told the Board of Trade enquiry; “Although I do not signal the Up Goods line I noticed that the goods train on that line passed my signal box at an unusually high rate of speed as though the Peckwash Sidings distant signal had been lowered for it, but on looking at that signal, I saw it was at danger”. He then went on to add; “The speed of the train was not such as to cause me to think that the driver would not be able to stop at Peckwash Sidings home signal”. This later point is significant as it was at this moment that he ‘pulled off’ on the Up Passenger for the Class ‘A’ express goods.

The next person to become concerned by the speed of the mineral train was Sidney Stiles in Peckwash Mill box. He had just had a flurry of activity having accepted and asked on a third goods train on the Down line in addition to the two trains approaching on the Up, and was entering the times in his train register. He looked up and saw the sight that every railwayman dreads, the mineral train was at his Up Goods Home signal and was still travelling at a speed too fast to stop. Stiles could only watch in horror as the train passed the signal, ran up the 45 yard long head shunt and through the stop block with a crash.

At that instant, neither the class ‘A’ goods on the Up Passenger, nor the train on the Down had been given ‘on line’. Stiles “threw back” all his signals and sent Six Bells (“Obstruction Danger”) to Duffield Junction and Little Eaton Junction. At this instant, the Class ‘A’ goods train on the Up Passenger was still between Duffield Station and Duffield Junction boxes.

Little Eaton responded to the “Obstruction Danger” signal with Six Bells indicating he had successful stopped the down train (otherwise the reply would have been 4 pause 5 pause 5 – “Train or Vehicles Running Away on Right Line”. However, Barnes in Duffield Junction had heard the bell code as the “cancelling signal” (3 beats, pause, 5 beats). He duly repeated that, put the block to ‘Normal’ and put back his Down signals, in the belief it was that train which had been cancelled.

Stiles, by now obviously alarmed at the events unfolding in front of him, sent Six Bells to Duffield Junction once more and both men came on the telephone to each other – Barnes to enquire what had happened to the Down train and Stiles to ensure the Class ‘A’ goods on the Up Passenger had been stopped. Stiles’ state of mind could not have been calmed by the news from Barnes that it was at that moment passing his Starting signal and his putting back of his signals was now fruitless.

Unbeknownst to all, the wreckage of the now derailed mineral train had fouled the wires of Peckwash Mill Siding’s signals. Thus, when Stiles put his Up Passenger Distant signal back to danger, the arm had remained in the ‘off’ position while ever Duffield Junction’s Up Passenger Starting signal above it was ‘off’.

On the footplate of the Class ‘A’ goods, as his train passed under a bridge, driver Partridge was alarmed to see the Peckwash Mill Sidings Up Passenger home signal at danger when he’d had “the back ‘un” off. He told the Board of Trade enquiry; “I closed the regulator and looked back to see if my train was following all right, and finding it was, I applied the steam brake, reversed the engine, and allowed sand to run on to the rails, and the fireman applied the hand brake on the tender. When near to the home signal I saw the signalman exhibiting a red light, but was unable to bring my train to a stand until after passing the home signal”. He brought his train down to a speed of five or six miles an hour when felt his engine strike something “pretty smart but not hard enough to throw us off the line”. The train came to a halt only “about a dozen yards” past the home signal.

Partridge had also given a series of ‘sharp blasts’ on his whistle as he had passed the rear of the mineral train on the Up Goods line. This had, of course, alerted the guard Quinby who was otherwise oblivious to the fate of his train. He had felt nothing untoward at all as his train came to a halt.

National Railway Museum (DY1043)

In the dark, none of the men were sure what had happened. Partridge got off his engine and approached the signal box. There he encountered Stiles in an agitated state saying that there was something the matter on the other side of his engine and he should go and look. Partridge went round to the nearside of his engine and saw that although its tender was still adjacent to the Up line, the loco of the mineral train had gone down the embankment at the end of the Up Goods Line and was buried by the limestone from the first six wagons which had toppled over on top of it.

After a fruitless search for Hitchcock and Teagle, driver Partridge turned his attention to protecting his train. Signalman Stiles was concerned because the weight of the wreckage on the signal wires was holding off the Up distant signals so he asked Partridge to go and cut the wires with a chisel.

The breakdown gang were summoned from Derby and their first act was to dig for the missing men. It was not until the six wagons on top of the engine had been lifted by a steam crane, some hours later, that their dead bodies were recovered from the foot plate of No. 1,433. The engine was down the embankment on its left side with its tender lying on its right side on the embankment. The rear of the tender was very close to the Up Passenger line, both the engine and tender being practically at right angles to the main line with the tender being described as slightly in advance of the engine.

On examining the engine, it was found that the reversing lever was fully reversed and the regulator was wide open. All six wheels of the engine, and all six wheels of the tender, were fitted with a steam brake applied by one steam cock from the foot-plate of the engine. This cock was wide open. The brake had therefore been fully applied and there were flat and discoloured places on the wheels of the engine and tender showing that they had skidded for some considerable distance. Indeed, this evidence is visible on photographs of the scene.

National Railway Museum (Derby Official DY1044)

The bodies of Hitchcock and Teagle were carried across the fields some three or four hundred yards to the Bridge Inn and attention turned to clearing the line. Mr. W.A.Mugliston, Superintendent of the Line, visited the scene, as did other leading officials of the Company. The efforts of the breakdown gang were such that by 8.0 a.m. traffic was once more resumed. By the following Monday morning, the only evidence of the events of Saturday morning was the remaining limestone spread about the area.

The damage to the Class ‘A’ goods train was limited to the engine and the first wagon being buffer-locked with the tender. This was rectified by the break-down gang and driver Partridge was able to take his train on to Little Eaton Junction, where it was placed it in a siding and Partridge drove the damaged engine to Derby.

At 2.30 p.m. the following Monday, Mr. F.E.Leech, Coroner for the Hundred of Appletree, which district embraces the parish of Duffield, sat at the Bridge Inn, Duffield, with a jury, for the purpose of inquiring into the deaths of Henry Hitchcock and Frederick Rueben Teagle. [This is the report in the Derby Daily Telegraph of Monday, 3rd December 1900].

The Coroner, in summing up, said that the only two people who could have thrown any light on this disaster were the two unfortunate men who met with their death. It seemed pretty clear, however, that Hitchcock misunderstood his signals. The latter must have been against Hitchcock, because the points that worked them on the same lever prevented him going on to the main line, as he intended, and sent him into the stop block.

The jury returned a verdict to the effect that the two men were accidentally killed by mistaking their signals and running their train into a siding with the result that they struck the stop block and were overturned.

That was not the end of the matter, Major J.E.Pringle conducted an enquiry for the Board of Trade. It could be said that his investigation was somewhat more knowledgeable and thorough than that carried out by H.M. Coroner. Maj. Pringle’s primary conclusion was thus;

The driver and fireman, who alone could have explained why they passed the latter signal at danger, paid the penalty with their lives for their fault. But the fault appears, from the circumstances of the case, to have been an error of judgement rather than wilful disregard or confusion of signals. The evidence proves the driver had had taken every possible step to stop his train before the collision took place. Signalman Barnes states that the goods train passed his box at an unusual speed, and the atmospheric conditions had evidently rendered the rails greasy. These facts point to the probability that the driver approached the junction at a somewhat higher rate of speed than that warranted by the falling gradient, the state of the rails, and the position of the signals, and consequently failed to get his heavy train under control in time to avoid a collision with the stop-block.

Whichever conclusion is correct – be it the Coroner’s view that Hitchcock misread his signals or Maj. Pringle’s that he misjudged his braking, it is apparent that responsibility lay with the driver. Teagle could only really have been an unwitting participant. The Major did have some minor words of criticism for others involved in the story;

As regards the second and minor collision, due to the fouling of the up passenger line by the overturned tender, it is possible that this might have been averted by the display of more coolness or alertness on the part of signalmen Stiles and Barnes and driver Partridge. But it would, I think be hypercritical to find fault with either of these men.

Barnes may indeed deserve a mild rebuke for failing to react to swiftly to the “Obstruction Danger” signal (it seems inconceivable that Stiles sent Six Bells one way and 3-5 the other!). However, to even begin to find fault with driver Partridge is outrageous! He brought his express train to a stand a mere 12 yards past the signal having had a clear Distant 744yds in rear of the Home signal concerned, with sighting restricted by an over bridge. This is the mark of a skilful and highly attentive driver.

Finally, Maj. Pringle turned his attention to the Midland Company;

Though it is impossible to prevent entirely the occurrence of such accidents due to errors of judgement, it is clearly of importance that at all such running junctions, especially on descending gradients, as long a catch-siding as possible be laid. In this instance, had 30 or 40 additional yards of rail been laid, the collision might not have had such distressing consequences. The Company will doubtless see their way to complete the embankment between the two stop blocks, and lengthen, so far as possible, the catch-siding for the up goods line.

Of course, the completion of the Up Goods Line from 5th January 1902 achieved just that.

On the Tuesday afternoon following his death, Henry Hitchcock was laid to rest in Derby’s Nottingham Road cemetery preceded by a service at the railwaymen’s’ church, St. Andrews. The Derby Daily Telegraph reported that “he was conveyed from his late residence in Fleet-street amid many manifestations of sorrow, and accompanied by a large concourse of sympathising friends”. Fred Teagle was buried in his home town of Sileby.

The final tribute to the two unfortunate footplate men was this poem by Signalman James Passey of Little Eaton Junction. It was published at one penny, the proceeds to be devoted to the widow and children of Driver Hitchcock and the widowed mother of Fireman Teagle:

A train left Derby Midland Station, Shirland was its destination.

Progress was slow, relief required, For the driver and the man who fired.

I telephoned for the relief, For the train which came to grief.

To be relieved at Ambergate, Little thinking of their fate,

That on their returning to their home, To which alas! they never come.

Through accident their life was took, Perhaps caused by a mistaken look.

Be that as it may, we'll try, To help and dry the mourners' eyes.

They need our sympathy and our aid, As no more wages will be paid.

To those who toil for daily bread, And shared the table's daily spread,

Father, mother, children three, Who prattled round poor Hitchcock's knee

Teagle was his mother's joys, A beautiful and loving boy,

She'll miss his bright and sunny face, Alas! There's none can take his place.

They are now gone but not forgotten if we do our duty well, Surely all

can do a little, for the bereaved a sum to swell.

I pen these lines by a request, From mate who want to do their best,

To help them in their hour of need. To widows and the children feed.

I gladly would have shirked the task, twas love impulsed the hearts who asked,

we all are brothers, or should be, But do not always seem to be.

The fatal spot was Peckwash Mill, Where paper is made with care and skill,

The buffer stop was struck with force, Although the engine was reversed.

Their best was, done but on they went, Till all their energy was spent,

Bravely to their post they stuck, And thus the thread of life was cut.

Engine fourteen thirty three, When overhauled you'll see again,

But the faces of the men On earth we'll never see again.

To one and all we now appeal, The leaflet price is not a deal,

Augment it more f'tis your will, I write no more my pen is still.

Dave Harris, Willington, Derby, UK.

Email: dave@derby-signalling.org.uk

Page last updated: Wednesday, 26 August 2015